Sounds of Bach

Music by Johann Sebastian Bach

Toccata

Fugue

Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier BWV 731

Chorale

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott BWV 720

Pedalexercitium in G minor BWV 598

Fantasia & Fugue in G Minor BWV 542

Fantasia

Fugue

Vater unser im Himmelreich BWV 737

O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig

Chorale

Prelude, Trio and Fugue in C major BWV 545 and 529

Prelude

Trio

Fugue

Pastorella

Allemanda

Aria

Giga

Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her BWV 738 (Tamburini Organ)

Herzlich tut mich verlangen BWV 727

Fantasia in G Major (Pièce d'Orgue) BWV 572

Très vitement

Gravement

Lentement

Total playing time 70m 37s

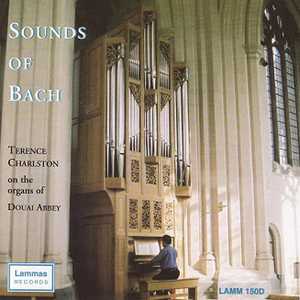

Sounds of Bach

Terrence Charlston plays the organs at Douai Abbey

Sounds of Bach

Terrence Charlston on the organs of Douai Abbey.

The Toccata & Fugue in D Minor BWV 565 is perhaps the most famous work in the entire organ repertoire. Hated and loved equally amongst organists, doubts have been cast over its original form (was it originally for solo violin?) and, inevitably, its parentage. Not surprisingly, it has assumed a life of its own and made its film debut in the 1940s courtesy of Walt Disney. On the concert platform it can be heard in every conceivable performance style: from solo violin (Andrew Manze and Maxim Vengarov, for example) to free bass accordion and through legion arrangements by artists as diverse as Busoni and Stokowsky. One of Bach's earliest works, it is written in three, contrasting sections. The famous opening toccata is followed by a lengthy spiel-fugue and concluding recitativo which returns to the improvisatory spirit of the opening passaggio. BWV 565 is particularly well suited to the Tickell organ and the clear but generous acoustics of Douai Abbey.

Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier BWV 731, like Herzlich tut mich verlangen, sets the chorale melody in the right hand with written-out ornamentation and figuration as if newly created. I append a simple version of the chorale based on BWV 702ii which represents the chorale tune in simpler form. Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott BWV 720 is also an early work, probably written for the inauguration of the Mulhausen organ, and in several sources it is transmitted with registration instructions. The youthful treatment of the melody, closely following the sentiments of Luther's famous chorale text, is well suited to the colourful registrations deployed over three manuals.

In the pantheon of Bach's organ works, the Fantasia & Fugue in G Minor BWV 542 stands in the place of honour. Also a youthful work, BWV 542 is traditionally associated with Bach's visit to Hamburg, where he (unsuccessfully) auditioned for the aged Reincken's organist post (a job which also included the hand of his daughter in marriage!) The sheer scope of both movements and the unprecedented length and difficulty of the fugue would have impressed any examination panel, but one wonders at the reception of the Fantasia's fearless use of chromaticism and reckless modulation scheme, which challenge the contemporary view of how an organ piece should sound and behave. The brilliant fugue subject is a quotation from Reincken's Hortus Musicus collection of Trio Sonatas: a homage to the master and a gauntlet to Bach's contemporaries. Copies of the fugue describe it as "the very best pedal piece by Bach". I preface this performance with the Pedalexercitium in G minor BWV 598, an incomplete fragment which may be a written-down extemporisation in the North German pedal-solo style, such as Bach may have demonstrated during his various trials for employment as an organist.

Vater unser im Himmelreich BWV 737 is exceptional among Bach's organ chorales for its motet-like texture much favoured by Scheidt and his followers. The equality of the part-writing and the lack of a distinct pedal character in the bass suggest this is for manuals alone. It is attributed to Bach by Walter. The paired settings of O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig are close to the chorale styles of Walter and Böhm. Also attributed to Bach by Walter, they are traditionally opera dubia (hence the lack of BWV number) but recently (1961) made it back into the canon of the organ works in the New Bach Edition (NBA).

It appears that organ recitals in Bach's day began with a prelude and ended with a fugue, and the pieces in between would be chosen to display the player's skill in choosing stops (for which Bach was renowned.) Today's familiar pairing of Preludes and Fugues was not always so hard and fast and several of the major works have a slow movement separating the first movement from its fugue. The Prelude and Fugue in C major BWV 545 is a case in point as it appears in one source with the Trio BWV 529 sandwiched as a central movement. The trio is better known as a slow movement in the organ Trio Sonatas, Bach's present to his favourite son, Wilhelm Friedemann. The Prelude underwent several revisions, and it is unclear if the first 3 bars and last 4 bars were part of the original. The Fugue is a splendid example of a ricercar-type of fugue in which its numerous thematic elements are combined in new and ever expanding permutations.

The Pastorella in F Major BWV 590 has its origins in the old Italian tradition that the shepherds descended from heaven to Rome playing music on Christmas night. Frescobaldi, Zipoli and Pasquini, amongst others wrote gently rocking pieces in compound time which featured a drone note in the pedals to imitate the shepherds bagpipes. Bach's piece is wrought as a suite of four movements. The first is the Pastorella proper, the remaining three are for manuals alone, an allemande, a c minor aria in expressive style and a gigue-fugue in 3 parts, with uncanny similarities to the finale of the third Brandenburg Concerto.

Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her BWV 738 transforms a simple four-part harmonisation into a continuous 12/8 semiquaver texture. The running figures, typical of many Christmas chorales, are symbolic of angels and bells. The setting of the celebrated Herzlich tut mich verlangen BWV 727 is found in the same source as O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig (this time in a later hand). As a meditation on death, the chorale is featured four times in the St.Matthew Passion. The organ setting intensifies its melancholic atmosphere by the choice of key and the conspicuous pathos of the figura suspirans.

The Fantasia in G Major BWV 572 has long been a favourite amongst church organists and the magnificent counterpoint of the five part central section is profoundly uplifting. In contrast to it, the opening section eschews polyphony in favour of brilliant passagework for the hands alone. The final section adds a descending chromatic pedal scale to the kaleidoscopic harmonies of the manual part. The title Pièce d'Orgue was adopted by Kenneth Gilbert and the editors of the New Bach Edition (NBA) as a more appropriate reflection of the Frenchified ornamentation and tempo indications in certain sources of BWV 572. I have chosen to play this tour-de-force using the typical French Classical registrations of the plein and grand jeux.

©Terence Charlston, 2002.

Terrence Charlston

Terence Charlston is widely acknowledged as one of Britain's leading Early Keyboard players. He has given concerts all over the world and has appeared on over 40 commercial CDs on harpsichord, organ, virginals, clavichord and fortepiano. For the National Trust, he has recorded all the playable keyboard instruments of the Fenton House Collection in Hampstead, London. His solo harpsichord recordings of Bach and Couperin for the Deux-Elles label have been greeted with critical acclaim. Since 1995 he has been a member of the ensemble London Baroque. He teaches at the Royal Academy of Music and has given master classes in Germany, USA and Mexico.

Born in Lancashire, he studied organ and harpsichord in Oxford and London, and was organ scholar at Keble College and Westminster Cathedral. He began his long association with Douai Abbey while he was Assistant Director of Music at Bradfield College. He has given many concerts at the Abbey including the last recital on the old Rushworth organ, which was dismantled when the Abbey was completed and the inaugural recital on the new Tickell Organ in 1994.

The Organs of Douai Abbey

The impetus for the development of the organ in the western Christian world came essentially from Benedictine monasteries. By AD 1000 the Benedictines had produced the biggest set of musical innovations known to music history; a repertory of chant, a practical theory of music and musical styles, musical notation and music drama. Benedictine technological advance was also to be found in architecture and engineering. The organ was a musical and technological salute to the maker of all things. The rows of pipes housed in a case symbolised the heavenly choirs of the house of heaven, the air flowing through the pipes the breath of the Spirit. From Greece and Byzantium, via the Christian court of Charlemagne the organ came to Anglo-Saxon England. In the 10th century St. Dunstan made an organ for Glastonbury Abbey and gave one to Malmesbury Abbey. At Abingdon, Aethelwold made an organ and at the royal Benedictine Abbey of Winchester Wulfstan, the Cantor, gave a detailed account of the organ in c.990, at which two monks of harmonious spirit sat together to play the organ, which was blown by 70 men dripping with much sweat.

From c.1000 AD organs are to be found in abbeys and other important churches throughout Europe. The oldest extant organ, now in Sion Conventual Church, in Switzerland, was originally from the nearby Abbey of Abondance. By the 18th century the organs of Abbeys such as St. Gall, Ottobeuron and Weingarten were tributes to monastic musical and technological development. Between 1766 and 1770 the most significant organ treatise ever written, the four volume L’Art du Facteur d’orgues, was written by a French Benedictine monk, Dom Bédos. The connection between the Benedictines and the organ is not surprising - the organ is both a symbolic and practical instrument with which to give praise to God: the praise of God, the liturgy, being central to Benedictine life and spirituality.

From their earliest days in exile after the reformation the Douai monks had organs in their monastery in Paris, the buildings of which are now the Schola Cantorum renowned for the training of many famous French musicians. In 1771 the Douai monks ordered an organ from France’s most famous organ-builder, F-H Cliquot. The Cliquot organ was finished in 1773 and was tried by Messrs. Couperin and Charpentier, and several organists in Paris and was found to be an exceedingly good one. Later, after leaving Paris at the Revolution, the monks had an organ in their church at Douai, possibly by Bishop or Cartier. After leaving France for Woolhampton, the monks first had an organ by Bevington and, after the building of the first stage of the Abbey Church in 1933 at Woolhampton, they installed an organ in 1938 by Rushworth & Dreaper, with Harold Darke as consultant, which was added to in 1947 and 1953. In 1979, in conjunction with a re-ordering of the church, a one-manual Italian organ was installed by Tamburini. The consultant was Dr. John Rowntree.

In 1993 the Douai community decided to complete the Abbey Church with a spacious western nave, with Dr. Michael Blee as architect, resulting in a building of great distinction. In conjunction with this a new organ was commissioned from Kenneth Tickell, again with Dr. John Rowntree, the Abbey Choirmaster and Organist, as consultant. The organ is free-standing in an oak case, with carved pipe-shades designed by Alan Caiger-Smith, the distinguished potter from nearby Aldermaston. The divisions are placed with the Echo above the key-desk, the Great at impost level, the Swell above the Great, and the Pedal in a separate case behind the main case. The result is an instrument of great musicality, well-fitted for its liturgical function, whether it is accompanying the monastic Latin or English chant, the music of choir or congregation, or appropriate organ music within the liturgy. The organ also plays a full part in concerts and recitals of music appropriate to the Abbey Church, which is first and foremost a house of prayer.

Dr. John Rowntree, 2002.

Recorded in Douai Abbey

on 16th and 17th September 2002

Recorded and edited by Lance Andrews

Cover photograph of the Tickell Organ by Lance Andrews