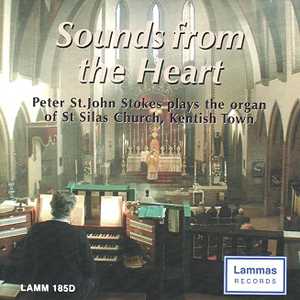

Sounds from the Heart

Peter St.John Stokes plays the Copeman Hart organ of St Silas Church, Kentish Town

from the Livre d’orgue Antoine Dornel

i Récit en taille

ii Basse et dessus de trompette

iii Récit en dialogue

Toccata and Fugue in D minor BWV 565 Johann Sebastian Bach

i Toccata

ii Fugue

Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Johann Sebastian Bach

Noël dans le goût de la symphonie-concertante Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier

Offertoire pour le jour de Pâques Alexandre Pierre François Boëly

Fantasia and Fugue on BACH Franz Liszt

i Fantasia

ii Fugue

from Sept pièces Théodore Dubois

i Interlude

ii Marcietta

Choral III in A minor César Franck

Total playing time 70m 44s

Sounds from the Heart

Sounds from the Heart

Offertoire in D minor Jean-François Dandrieu (1681 or 2 – 1738)

The great classical tradition of French organ composition was brought to perfection by such illustrious names as Francois Couperin and Nicolas de Grigny. Like the rest of French music in the grand siècle it was increasingly subject to Italian influences. Dandrieu was of the next generation of composers and his Livre d’orgue can be seen as at the turning point between the older French and the newer Italian styles. He was organist of St. Merri and became one of the four Organistes du Roy who took turns in playing at the Royal Chapel, but he is probably best known as a composer of music for strings in a style which reflects very strongly the influence of Corelli. The organist’s duty in France at that time involved playing short versets in alternation with the choir and a longer piece as the altar was prepared at the offertory. It was usual for these offertoires to be scored for the wonderful, and uniquely French, sonority of the grand jeux, which is the reeds together with the bourdon 8, prestant 4 and cornet V. This piece is in fact a re-composition of the first two movements of one of his trio sonatas. The opening, marked gravement, is a blend of the slow opening of a French overture and the Italianate use of strong chord progressions and sequences. The marqué section, despite being headed by the 18th century French equivalent of allegro, is a very thoroughly worked out fugue, again in the Italian manner. The opening exposition ends in F major and is followed by a central section in two parts, the right hand being on the cornet and the left on the cromorne. Evidence of the composer’s abundant and renowned contrapuntal ability is shown in the final section where a new countersubject is placed alongside the original.

from the Livre d’orgue Antoine Dornel (c1680 - after 1756)

i Récit en taille

ii Basse et dessus de trompette

iii Récit en dialogue

Dornel was another composer from the early years of the 18th century, who, in much of his music, showed a marked preference for the Italian style. However these pieces have been chosen from among those in his music that show a strong respect for the French tradition of the past. They are all short as they are versets, which were short pieces that were played in alternation with the plainchant of the mass or of vespers. The Récit en taille was a commonplace of the classical tradition, in which the tune is played in the left hand with the accompaniment in the right hand and on the pedals. This calls to mind the many beautiful and elegiac pieces that were written by composers such as Colombe and Marais for the viola de gamba with continuo accompaniment. The Basse et dessus de trompette was a favourite form for the organists to show off their digital dexterity on these stops with their very rapid response to the players’ touch. Finally the Récit en dialogue is a wonderfully expressive movement, using the distinctive and spicy sonorities of the cornet and the cromorne. In the first section the solo voices are accompanied by the left hand. In the second they are in a trio with the pedals playing the bass. This music is suggestive of the delicately ornamented singing of the French opera of the period, while the elegant balance of its phrases recalls the expressive symmetry of the alexandrines of Molière or Racine.

Toccata and Fugue in D minor BWV 565 Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 – 1750)

Opinions differ about the origin of Bach’s best known organ piece to such an extent that some would say it is not even by the great master himself. The problem with not attributing the piece to Bach is that there is no one else who can be considered as the likely composer. What is even more convincing as an argument for the attribution of this piece to Bach is that he was the only composer to show such a variety of approaches to the prelude and fugue format that could encompass this work along with the rich variety of the others. A likely suggestion is that it was originally a piece for solo violin, probably in the key of A or G minor and was transposed into D minor to take full advantage of the dramatic effect of the low tonic in the organ pedals. It must be borne in mind that Bach was himself a violinist and that this is quite possibly an early attempt at this process of arranging material from a solo violin piece that was manifested in his maturity by the so-called ‘Fiddle’ Fugue. The intense drama of the opening toccata and the chromatic intensity of the end could be considered as a forerunner of the great toccata in G minor.

This piece’s popularity is well deserved. In the toccata Bach has taken the sectional method of composition of Buxtehude and his other North German predecessors and given it his characteristic dramatic and rhetorical intensity. The fugue subject, having the same melodic outline, is obviously derived from the opening of the toccata. The movement is divided into four sections. The first is a fugal exposition of a light and vigorous character reminiscent of the dance. This gives way to a passage with figuration of a violinistic nature that nevertheless exploits brilliantly the echo effects available using the different manuals of the organ. The third section, with its rapid scale passages and its showy pedal writing, suggests contrapuntal virtuosity. The final section manages a return to the spirit of the toccata without actually repeating anything from it. The piece ends, not with a blaze of glory, but with a sombre homophonic passage ending with a dark minor chord.

The whole is exactly the sort of piece that Daniel Gottlob Türk must have been thinking about when he wrote, only 37 years after Bach’s death, about the voluntary after a service.

“On the whole they are the same as the common prelude, although a fugue would have a fitting place here as well. Perhaps this would be the most opportune time for the organist to demonstrate his proficiency, to incorporate a pedal solo, and to employ everything his art makes available to him. Should he stray too far afield in this, the nuisance he causes as a result will not be of great consequence because the majority of the congregation will no longer hear him.”

‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring’ has long been popular as an arrangement. The original is from cantata 147, ‘Herz und Mund und That und Leben’, where the flowing triplet melody is played by violins and oboes in unison and the chorale is sung by the choir in four parts. The version played here takes as its model the organ preludes, arranged by Bach himself from movements from his own cantatas, published as the six Schübler preludes. In these the texture is often much reduced to make a clear and idiomatic organ piece. Here the triplet melody is played on flute stops, the basso continuo is played on the pedals and the melody is ornamented and played on the jeu de tierce.

Noël dans le goût de la symphonie-concertante Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier (1734 – 1794)

Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier was one of the organists of Notre Dame de Paris in the years leading up to the revolution. In his music the movement towards Italianisation that is apparent in the works of Dandrieu had reached the stage when the organists reflected the style of what had become a more or less unified European musical culture. This piece is nonetheless interesting as it successfully combines three elements. The first is that of the organ Noël based on French Christmas carol tunes, which were very popular pieces for the liturgy at Christmastide, where a piece of this length would almost certainly have been used as an offertoire. The second element is that of the symphonie-concertante, which with its solo elements was more popular in France than the symphony. Finally it is a set of variations in the classical style and very much in the manner of the famous variations by Mozart and Beethoven. The theme is the carol ‘Ou s’en vont ces gays bergers’, and we are treated to eight variations which fully explore the variety of effects available on the French organ by the end of the 18th century. These include numerous echo effects and the much deeper and more massive sound available since the introduction of the Bombarde at 16 foot pitch earlier in the century.

Offertoire pour la messe du Jeudi saint

Offertoire pour le jour de Pâques Alexandre Pierre François Boëly (1785 – 1858)

Boëly was a composer of great merit. He was somewhat overlooked and misunderstood, both in his lifetime and subsequently. Recently a reassessment of his work has taken place and a significant new complete edition of his organ music has been published under the inspiration of Nanon Bertrand-Tourneur. This reveals him to have been a composer of great integrity, with a distinct and highly developed harmonic style, great contrapuntal facility and an ability to combine in his style the developments in the wider European musical scene. A particular influence was the music of Beethoven and this is particularly evident in the second of these pieces.

The Offertoire for Maundy Thursday was composed for the mass which commemorates the institution of the Eucharist. It powerfully suggests the coming Passion, being full of dark and gloomy foreboding. The texture of the music which is cast in the form of the instrumental trio sonata movement looks back to the 17th and early 18th centuries. However this is not cast, in the manner of the German composers, as a trio for two manuals and pedals but is here played on the uniquely French combination of cromorne avec les fonds. This requires the use of the smoother classical version of the cromorne in ensemble with all the 16 and 8 foot flue stops. Boëly’s use of harmony and controlled dissonance throughout the even texture of a sustained movement demonstrates his compositional ability.

Not surprisingly Easter Day is given a very different sort of piece. This was probably written for the large Clicquot organ of St. Gervais in Paris, which was still very much an instrument of the classical French tradition. This piece however is the first to have directions for stop changes during the course of the movement. The opening, the nature of which is surely inspired by Beethoven, suggests the rising from the darkness of the tomb. Here it is still the classical grand jeu of Dandrieu’s music with the addition of the 16ft. bombarde which is used in its continuation down in the pedals into the 32ft. octave to express the darkness of the tomb before the Resurrection. This exciting opening must have sounded terrifying to contemporary worshippers. It is followed by a statement of the ancient hymn, O Filii et Filiae, (O Sons and daughters let us sing) which is followed by two variations ending with a downwards chromatic scale that leads into a short but exciting fugue. Although in this piece, as in so much of Boëly’s music, it is easy to imagine him struggling to express his romantic ideas against the restraints of the French organ of his day, it is nevertheless one of the most impressive musical expressions of the Easter story.

Fantasia and Fugue on BACH Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886)

According to Liszt’s pupil and friend Alexander Gottschalg, he was a capable organist, being very imaginative in his registrations but not too brilliant in his use of the pedals. He must have been very interested in the instrument because while he was in Leipzig the two musicians used to travel round the area to play many of the interesting organs that had remained untouched since Bach’s time. This composition however suggests that it was inspired by the potential of the large-scale romantic instruments that were being built at the time. It is a work of dramatic, almost violent, contrasts and brings the world of romantic pianism, with all its emotional and virtuosic display, into the organ loft. The letters BACH give in German: B flat – A – C – B natural. Bach himself introduced it into his final unfinished piece in the Art of Fugue. Liszt takes this motif out of Bach’s fugal context and uses it right from the opening as a rather dark and powerful emotive statement on which to base this most dramatic music. This piece, in its attempt to combine romantic virtuoso writing, symphonic development techniques and the prelude and fugue format, is interesting enough, but Liszt also chooses to complicate matters further by making use of traditional Hungarian scales.

The Fantasia is very freely composed and is reliant for its unity of the frequent recurrence of this motif. It starts very strongly and moves with intensity to a short quiet passage. There is then a swift and virtuosic crescendo to a harmonised statement of the motif on full organ. A descending scale, not chromatic but in the form of one of the traditional Hungarian scales, leads to the first entry of the subject.

The Fugue starts off with what at first appears to be a conventional exposition. The first statement of the subject has a false start with a statement of the motif in a remote key. After the fourth entry more conventionally romantic techniques of symphonic development take over. This is passed through many keys and a dazzling variety of textures, including a lengthy passage with octaves in both hands. The theme finally reappears in the pedals in the original key with a succession of diminished seventh chords above. This moves sequentially up to the remote key of B major before a coda that exploits the full range of the organ’s dynamics.

from Sept pièces Théodore Dubois (1837 – 1924)

i Interlude

ii Marcietta

Dubois, although known mostly today as a composer of organ music, was in his lifetime one of the leading French composers. He wrote church music and oratorios but seemed to be most at home in the opera house, having composed both grand operas and operettas. Like many of the leading figures in French music he was an organist. In 1877 he replaced Saint-Saëns as organist of the Madeleine, and he wrote a large number of organ pieces. To the composition of many of these, including the ‘Sept pièces’, he brought all the melodic skill of the operatic composer and each piece has a very distinct character. The Interlude uses the hautbois stop in its treble and tenor registers in alternation with a flûte. The Marcietta is an amusing miniature that uses the fonds de 8 pieds, usually reserved for rather solemn music, for a piece that has much of the character of a scherzo.

Choral III in A minor César Franck (1822 – 1890)

Franck was another of the major figures in Parisian music of the 18th century. From early in his Parisian career he was organist of St Jean-St François in the Marais and associated with the organ builder, Cavaillé-Coll. He became known for his phenomenal improvisatory powers, and in 1858 he became organist of the newly built basilica of Ste. Clothilde, which had a splendid new organ by Cavaillé-Coll. The difference between this type of organ and that which Boëly played was that the latest technologies were used to enable a smooth and gradual crescendo and diminuendo by the use of pedals, so that the flow of the music in the manuals was not disrupted by stop changes. With this and the newly invented imitative voices, this type of organ could be truly described as symphonic. Franck wrote many pieces for the organ and in the summer before his death he completed his ‘Trois chorals’, so this is the last work he wrote.

It is not easy to understand why the composer gave these pieces the title ‘Choral’. It has nothing to with the German idea of a chorale, as these are long symphonic compositions based on a flowing melody. The third Choral opens with a fanfare-like section, requiring the somewhat unusual sonority of all the eight-foot flue and reed stops together. After a diminuendo, a chorale-like theme is played on the récit manual so that the expressive possibilities of the swell box could be applied to the music. This is interrupted by a quiet return of the opening, resumed and then made to give way to a crescendo leading to a dominant seventh. There is then the most beautiful extended melody in A major, which is in its proportions a microcosm of the entire piece. This gives way to a quieter passage but which leads to the most thrilling gradual crescendo. Confirmation of the composer’s symphonic intentions is given in that, while going through this piece on the piano with his pupil Charles Tournemire playing the pedal part, Franck asked that, in the loud passage here, the bass should be detached as if it were being played by trombones. The final section has much of the character of a toccata. It starts quietly but builds up quite rapidly to full organ and a return of the chorale-like theme which presses on to the massive chords of the ending.

Peter St.John Stokes

St Albans 2005

Peter St.John Stokes

Peter St.John Stokes was born in Scarborough, Yorkshire. He began to play the organ at school and at the age of sixteen he became a pupil of Francis Jackson, organist of York Minster. For years later he went to London to study at Trinity College of Music. Here he not only had organ lessons but also broadened his musical outlook by studying singing, orchestral conducting and composition. A particular influence was lessons with Dr Arnold Cooke, one of the most distinguished teachers of composition of the time. He has also studied improvisation with Naji Hakim, who is Messiaen’s successor at the Trinité in Paris. In addition to his musical qualifications he is qualified to teach photography and has a degree in French from London University.

From 1967 to 1994 he worked full-time as a teacher, for the last 21 years as Head of Music at Loreto College, St.Albans, a Roman Catholic girls comprehensive school with very high academic standards and a lively music department. A feature of his time there was the oratorio concerts including such works as Handel oratorios, the Bach Passions and the Mozart Requiem. The choir not only gave concerts and sang the services in the school but also sang in St Albans Cathedral and Westminster Cathedral. It also did concert tours of Francs and Belgium in addition to radio and other recordings.

While still a student he became organist of St. Mark’s, Marylebone. His organist appointments include St. Giles-in-the-Fields and Dunstable Priory. Since 1992 he has been organist at St. Silas, Kentish Town. He continues to teach the piano, organ and composition. He also writes articles on music including recently one on Boëly and another on French organ music of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Organ

St Silas, Kentish Town is the church of a large inner-city London parish, just to the north of the centre. When it was finished, just before First World War, it stood out high among the rows of terraced housing. Now it is in the middle of massive blocks of flats, but these shelter it from much of the noise of London traffic. The church therefore is much sought after for recordings, as it is both quiet and has an excellent acoustic with just the right amount of resonance to enrich the sound without confusing it.

Like many churches in the area, the parish follows the Anglo-Catholic tradition. In fact it is well known for the splendour of its decoration and its liturgy. Although a small choir of parishioners sing for the Sunday mass, there are several occasions each year when advantage is taken of the large gallery to use professional singers and instrumentalists to perform mass settings or vespers by composers such as Mozart, Haydn and Schubert.

Shortly after the church was built an organ was placed on the west wall. A console, with tubular pneumatic action, was placed on the floor of the gallery beneath and facing east. The organ had no stops above 4ft pitch and, although there were some attractive voices, had little balance between departments and individual registers. By the 1990s this organ had become effectively unplayable, and in view of its limitations it was decided to investigate the possibilities of substantial rebuilding or replacement. The accessibility problems and the limited space in the case made rebuilding this organ, with even just a few improvements, prohibitively expensive for such an inner-city parish. Because of the type of services and the large part organ music plays in the liturgy a new small organ would not have been effective. In any case the church already possesses a seven stop chamber organ, built in 1772 by Jonas Ley.

After much thought and investigation, it was decided to ask Copeman Hart to provide an instrument, which would be adequate for the occasions when the church is full and at the same time would have the necessary voices to enrich the liturgy and for choral accompaniment. This was installed in 1994, being built according to the specification of Peter St.John Stokes. Voicing was done in the church by Ernest Hart in consultation with the organist, and the flexibility of the system has allowed for both hardware and software upgrades, together with improvements in the original voicing. It has proved itself well suited to the church and its needs. It copes particularly well with French music, including that of the baroque, and is a good instrument for the music of Bach. Above all it has a real and lively presence in the church and fulfils its liturgical task excellently.

Recorded and edited by Lance Andrews

Photograph by John Salmon